Solving the Pendulum Problem

Intro

In the Spring of 2024 a new LLM evaluation called Humanity’s Last Exam was released.

A co-worker sent me the demo page at the time and I found a physics problem relating to a pendulum with a pivot point that slides along the

NOTE: The following presumes understanding of single variable calculus, the chain rule, trig functions, trig identities, free body diagrams, and newton’s second law.

Problem Statement

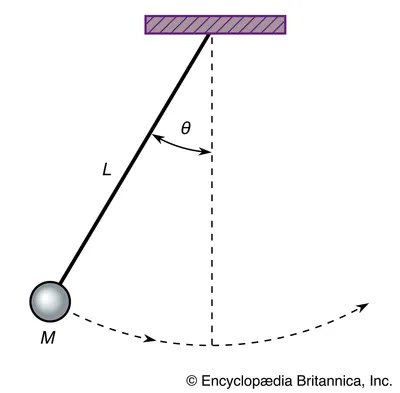

A massless rod of length

Deriving the Differential Equation

First, we use the laws of mechanics to derive a relation between

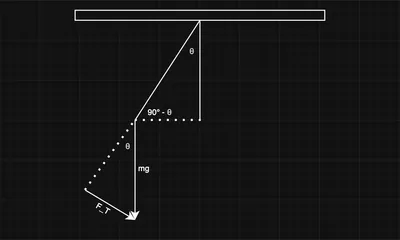

While the pendulum is displaced from the vertical, part of the downward gravitational force is acting on the pendulum tangent to its circular path.

Using trigonometry, we can find the magnitude of the tangential component of the

According to Newton’s Second Law of Motion, the absolute value of the force tangent to the path must be equal to mass,

Note that a symbol with a dot over it represents the time derivative of that value e.g.

, .

Thus,

Eq. 6 tells us that the magnitude of the force acting along the path of the swinging mass will be equal to

Should

Travel along the circular path is analogous to travel along the standard

We must find a

As we’ll see, this is easier said than done.

This difficult equation is often simplified by substituting

Although I facetiously referred to this approximation as “heinous” in the introduction, it’s useful to go through the solution before dealing with the complexity introduced by

Solving the Small Angle Approximated Pendulum Problem

The simplified differential equation.

We want to dump the second derivative on the left hand side through integration.

If we were to naively integrate both sides of Eq. 12, it would maintain equality but would not be productive.

Given that

Multiply both sides by

Integrate both sides with respect to

Solve For

Substitute the

Solve for

To integrate away this last

The integral can’t be evaluated using standard polynomial integration rules.

We rely on a visual match to the integral definition of

Click to See Derivation

Solve for

Substitute

Take the the

Simplify by substituting

Rearrange to find

To Summarize, we

- Used integration to turn

and solved quickly for the first constant of integration using initial conditions - Separated variables to produce an equation of the form

- Identified the integral on the right hand side to match the integral definition of

- Substituted

into the equation and solved for the second constant of integration - Took

of both sides - Solved for

This approach is mirrored for the Non-Linear Differential Equation.

Solving the Non-Linear Differential Equation

We start with the exact pendulum differential equation.

Multiply both sides with

Integrate both sides with respect to

Find

Substitute the calculated

Solve for

Rearrange to separate variables.

Now we see why the Small Angle Approximation is so helpful.

After the separation of variables, the integral exactly matched that of a well known function,

We hypothesize that we can algebraically manipulate the equation such that the integral on the right hand side matches that of

The first guess (spoiler alert, it will work!) is

I’ve seen it written in two forms: Legendre’s Form

and Jacobi’s Form where

We’ll use Legendre’s Form.

Note that

is a constant value, also called the Elliptic modulus.

This is a reasonable guess for two reasons. First, elliptic sine is periodic which matches the observed behavior of the pendulum. Second, it’s not algebraically distant. After a substitution into Eq. 37 based on the half angle identity,

it’s closer but not an exact match.

The denominator doesn’t match that of the IEIFK exactly.

This doesn’t mean it’s game over, we just need to define a new variable,

Upon substitution into Eq. 42 the numerator

Unfortunately, this is another educated guess and check.

Steps toward simplicity are generally productive.

Taking a look at the denominator, if we can change the

Hypothesize

Close, but then the numerator remains its ugly self.

However, this attempt highlights another opportunity.

If we take

Additionally, taking

Now we check the hypothesis by differentiating with respect to

This matches the end of Eq. 47. Apply the simplifications from Eq. 46 and Eq. 47 in reverse.

To summarize this step, we derived

Substitute Eq. 51 into Eq. 42 remembering that we defined

Integrate both sides. Definite integrals are needed to match the exact form of the IEIFK. This preserves equality.

Some insist on changing the variable inside the expression (e.g.

and ) so it’s different from the integral upper limit ( and ). Eq. 53 may be improper or even “wrong”, but I find it easier to follow in this specific instance.

Substitute

Solve for

For the sake of brevity, we’ll leave

Take the

Substitute

Solve for

Q.E.D.

To Summarize, we

- Used integration to turn

and solved quickly for the first constant of integration using initial conditions. - Separated variables to produce an equation of the form

. - Identified that

couldn’t be evaluated and manipulation would be needed to substitute for some . Nothing was an exact match off the bat. - Targeted the Incomplete Elliptic Integral of the First Kind for the right hand side due to the periodic nature of

and algebraic proximity. - Made a substitution based on the half angle identity and then defined a new “utility” variable

to get it to match up exactly. - Substituted

and solved for the second constant of integration. - Took

of both sides. - Solved for

. - Used the relation between

and defined in Step 5 to solve for .

Hopefully, this article made the Pendulum Problem less of a mystery.

Comparison of the Exact and Approximate Functions

For each frame, the pendulum position is calculated in your browser using the two

Sources

Pendulums and Elliptic Integrals published in 2004 by James Crawford was extraordinarily helpful.

I used the same algebraic path with some more explanatory notes and one minor error fixed.

Crawford adds a lot of detail about numerical methods which I didn’t touch on here.

It’s definitely worth a read if you’re interested in computation of

I also studied Edmund Whittaker’s solution in Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies. The old textbook has had pretty remarkable longevity given how much time I spent staring at it 122 years after publication. I found the content to be very thorough, even taking into account a pendulum which is given some starting speed*. It’s definitely worth a read if you are interested in “gloves off” Classical Mechanics.

*You then have to consider the case where the starting speed takes the pendulum over the top leading to two separate equations of motion.

Thanks Boys 🫡